Acadian survival in New England - some will find it presumptuous of me to undertake to write about such a topic. It is of course true that many descendants of old Acadia have forgotten their origins and have voluntarily allowed themselves to blend into the "melting pot". There are some who prefer not to be identified as Acadians. Basing themselves solely on persons such as these, others have made of them a general rule: "De uno, dice omnes." i.e. what can be said of one can be said of all. I have observed that people in certain areas of old Acadia have the impression that a person ceases to be Acadian after moving to New England. More than once, when I still lived in the United States, I would be scowled at for introducing myself as an Acadian. I was considered to be a renegade, a traitor. No, the Acadians of New England are not renegades of old Acadia, just as their ancestors who came to Acadia were not renegades of old France.

It is true that living in a milieu that is not French presents a grave danger to Acadians, just as it does for the French Canadians - that of losing the heritage left to them by their forebears. The worst of these losses, you will agree, is that of one's mother tongue, which is, as Acadians would say, "quasiment inévitable" almost inevitable. Robert Rumilly, in his book Histoire des Franco-Américains (1958), writes that in the United States, the preponderance of English quickly reduces French to the role of a second language, a foreign language, a dead language, or a luxury language. Please note, however, that it is not only in the United States that one can find many Acadians who no longer speak French; unfortunately, the very same thing happens in too many areas of the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

The question which needs to be raised here is whether or not there can be an Acadian survival without the French language. In other words, should we apply to the concept of Acadian survival what used to be said about the preservation of faith, namely, that one's language is the guardian of one's faith? Not necessarily. Language is certainly a great advantage; no one can deny that fact. But there are other factors which can contribute to the survival of a spirit, of traditions, and of an attachment to the past. In this regard, Rve. Édouard Hamon, in his book Les Canadiens-Français de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, assigns to religion a role equal to that of language as the guardian of the nationality of a people. When I was still living in New England, my purpose was to make their own history known to Acadians, in order to make them love their past and the Acadia of their ancestors.

It is true that, were one to base oneself on authors, one would have to conclude that Acadian survival is non-existent in New England. In fact, almost no historian of the Franco-Americans mentions Acadian survival. Worse than that, all of those historians, almost to a man, seem to be completely ignorant of the very presence of Acadians in New England. Brother Antoine Bernard, C.S.C., for instance, who in his book L'histoire de la survivance acadienne, devotes a chapter or two to each of the Maritime provinces, as well as to Quebec, the Magdalen Islands, Gaspé, even Labrador, writes not one single word about the Acadians of New England, not only in this book, but also in all the others he has wriitten on the history of the Acadians, except for one brief reference to La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption which was founded in New England. [Initially a mutual benefit society founded in Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1903, as an insurance society for the protection of the Acadians.] Hamon is just as silent. In his 550 pages on Franco-Americans, Rumilly did not think he owed more than five short paragraphs to the Acadians. In the second edition of his La Tragédie d'un peuple, Emile Lauvrière, devotes thirty-four pages to the topic of the "Acadian renascence", in New England. In thirty-one of the thirty-four pages, he writes about the French Canadians. Only three pages refer to the Acadians. It is useless, therefore, to look for anything pertaining to the Acadian survival in New England in these works. Either their authors did not believe it to be possible, or they knew nothing about it.

And yet Acadia has not died in New England. It lives on, if not among all Acadians, at least among a good-sized group of them who, while being very good Americans, are proud to call themselves Acadians. Those who remain attached to their country of origin, its traditions, its customs, and especially its history are quite numerous. One must not say, Loin des yeux, loin du coeur i.e. out of sight, out of mind, for many of these Acadians are more truly Acadian than many of their counterparts in today's Acadia.

Let us examine what has transpired since the first contingents of Acadians arrived in New England. According to my research on the demographic statistics of the Acadians in Massachusetts at the Bureau of Vital Statistics in Boston, there were a few marriages of Acadians during the decade of the 1850s, particularly in the fishing ports. There were about twenty in the 1860s. Then, in 1870, and especially in 1871, Acadian immigration started to expand, with the number of births, marriages, and deaths increasing constanly. These were mostly fishermen coming to seek their fortune along the American coast. The early ones came from Cape Breton, especially from Arichat, and then from the southern part of Nova Scotia. Consequently, Acadian women being rare at first, some of the marriages contracted were with American women. However, during the 1860s, especially in the second half of the decade, Acadian women accompanied their men at the start of the fishing season in order to come to Massachusetts to work in the cod industry. But almost all would return home to Nova Scotia at the end of the fishing season.

I studied the marriages contracted in Massachusetts between 1854 and 1880 by Acadians, from the southern part of Nova Scotia in particular, to which I added a few from Madame Island on Cape Breton. I found that during those twenty-seven years there were one hundred twenty-seven marriages of which only thirty-five, or 27.5%, wee contracted by Acadian men with Acadian women. Of the other ninety-two, or 72.5%, a few marriages were contracted with persons from the province of Quebec, the rest were with Anglophones. In all likelihood, this ratio also applies to the marriages of all Acadian immigrants of the same period. It is, therefore, difficult to imagine that there could have been an Acadian survival one hundred years ago for three quarters or so of the Acadians who had married in New England.

Those were not, however, the only Acadian families in New England. In the early 19870s, already-constituted families of Acadians began to migrate as family units to New England. In all likelihood, the lifestyle of these families continued much the same as had been the case in Acadia before their departure, at least within the home - a family does not change its customs overnight. But away from home, on the strets or in the factories, Acadians had to act like Americans. They could not do otherwise in an era when President Theodore Roosevelt was writing: We must be Americans and nothing else; or again when he stated that the United States must become an immense house of polyglot boarders. This was an era when Acadians could see signs displayed in store windows, or on the walls of factories, which read: Help wanted. Catholics or aliens need not apply. It is during this period that the Aucoin name became Wedge, Chiasson became Chisholm, Doiron became Durant, Fougère became Frazier, Girouard became Gillwar, Leblanc became White, Poirier became Perry - to mention but a few. Acadians at home, but on the street or at work, Americans only. Could the Acadian spirit survive in such an atmosphere?

It is, therefore, useless to look for any Acadian activity during those early years, since the newcomers were fishermen, factory workers, or laborers whose first thought was to ensure the basic necessities of life. I found the records of eighty-two Acadians living in Massachusetts between 1854 and 1880, and exactly half of them, i.e., forty-one, were fishermen; twenty-one, or one quarter, were hired hands or farmers; there were also thirteen carpenters, five shoemakers, and four carters. Of the remaining either, one was a boat builder, one a mason, one a painter, one a sail-maker, one an iceman, and so forth. There were no professionals, unless you want to classify a male nurse as such.

One can understand then why Rameau de Saint-Père, during his journey to America, in 1860-61, having gone to Boston, lauded the efforts of the French Canadians to remain Catholic and to preserve their hereditary language while making no mention of Acadians, the study of whom was, nonetheless, one of the principal reasons for his journey. He does, however, name one Acadian, probably the only one he visited, name Louis Surette, a native of southern Nova Scotia, whose mother was a d'Entremont. He says of Louis that he built up his own fortune, first as a sailor, fisherman, and coaster, trading from port to port along the coast, then as a store clerk in Boston, before adding, He is at the head of an important enterprise and sends his ships to all parts of the world. Louis Surette is the only Acadian of the period to have left us, in writing, an account of his participation in Acadian affairs, as revealed by the large number of his handwritten letters, as well as many newspaper articles, which I have in my possession. Most of his letters and the newspaper articles deal with Acadian matters: history, genealogy, customs. I have the reports of Acadian meetings which took place at his home in Concord, Massachusetts, as early as the 1860s, but more especially from 1870 on.

Louis Surette notwithstanding, it can be said that, in the early period, one has to go to Maine, especially, if not solely, to ascertain the efforts of the New England Acadians to remain Acadian. The proximity of Maine to New Brunswick made this possible. Thus, in 1880, when forty or so Acadians from the Maritimes responded to the invitation of the Société St-Jean-Baptiste of Quebec to attend their national convention, the State of Maine is mentioned. We should point out, however, that when one speaks of Acadians of Maine at that time, we are referring especially to those people of the American Madawaska who are usually considered historically as belonging to the New Brunswick group. They are the descendantas of the two thousand or so Acadians that the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 severed from New Brunswick to incorporate them into American territory. Additionally, during the 1840s, numerous Acadians of the Madawaska Region, along with French Canadians from the Beauce Region drifted to the lumber camps and mills of Skowhegan, Waterville, Augusta, and Belfast, and then later on toward Lewiston and Biddeford, where their descendants can still be found.

At the first Acadian Convention held at Memramcook, New Brunswick, in 1881 - the year following the Quebec Convention - the feast of the Assumption, August 15, was chosen as the national holiday of the Acadians. It would seem that New England was not represented, and for good reason: only the parishes of the Maritime Provinces had been invited. If the letter of Rameau de Saint-Père, responding to the invitation he had received, had not arrived too late, New England might have been represented, at least the State of Maine. For, in his answer, Saint-Père wrote: I think it would be helpful to make contact with the Acadians of Maine who are your next door neighbors... They should, on every occasion, be considered as belonging to your group. Had they been present, I wonder what their reaction would have been to the statement of one of the orators, Sir Hector Langevin, Minister of Public Works for Canada, who told the delegates: Do not emigrate to the United States; stay in your beautiful Acadia, especially you intelligent young men... don't go... ruin your health in the enslaving labor of American factories and mills.

At the second Convention held at Miscouche on Prince Edward Island, when the Acadian flag and national anthem were chosen, Rameau de Saint-Père's letter had been heeded. An invitation to attend had been sent to the Acadians of the State of Maine. However, I could not find the name of any Acadian delegate from that State, nor, it stands to reason, from any other part of New England. Would that have bedn why they believed t hat Acadians who had gone to the United Stated had already lost their identity and did not care to be recognized as Acadians any long? Whatever the reason, from the very first session, the plague of emigration to the United States was brought to the fore when a resolution was adopted to use every means possible to stem thetide which was reaching alarming proportions.

As one can readily see, there could not have been any significant Acadian activity in New England in comparison to the activity of the French Canadians from the province of Quebec, who, more numerous and generally coming from a more developed culture, were organizing themselves and expanding rapidly. In fact, these Canadians atracted a number of Acadians into their societies by showing them the benefit they could derive for their own improvement and perhaps even for the preservation of their Acadian spirit.

It seems, then, that during the 1880s, the Acadians of New England began to awaken, especially with the arrival of alumni from le collège Saint-Joseph of Memramcook, founded in 1864, by Holy Cross Fathers from Montreal, and those of le collège Saint-Louis, founded in 1874, by Monsignor Marcel-François Richard.

[The old system of collèges classiques consisted of a course of studies lasting eight years, roughly corresponding to the American high school and college systems combined. Thus, one could enter a collège as early as age twelve or thirteen-Editor]

Confining ourselves for the moment to the Acadian Conventions, according to the reports of the time, we finally find some Acadians from the United States at the third one, which was held at Church Point, Nova Scotia, in 1890. They are not identified by name; what is mentioned is the presence of a representative group from Haverhill, Massachusetts. Acadians were thus beginning to take cognizance of themselves even though this was true of a small number only.

The contacts which the Acadians of New England were beginning to set up at that time with the Acadians of the Maritimes greatly contributed to the awakening of the Acadian spirit among the former. I am referring at this point, not so much to social contacts with family and relatives, but to contacts pertaining to Acadian matters, such as history, genealogy, culture, language, in a word to anyhting t hat touched upon the Acadian issue in New England as much as in the Maritimes. Acadian newspapers, such as L'Évangéline, Le Moniteur Acadien, Le Courrier de Bathurst already had a number of subscribers in New England. In the voluminous corresonpondence exchanged before 1890 hbetween my uncle Léander d'Entremont of Peabody, who always took an interest in the history of the Acadians, and Louis Surette, whom I mentioned earlier, I find references to articles on Acadian topics published by the one or the other in those newspapers. I still have some copies of these articles. Both men also corresponded with the old-timers of their region, and elsewhere even, in order to learn more about the history and genealogy of Acadians. They then provided information to authors who were proposing to write, or indeed did write the history of the Acadians. In the case of Mr. Surette, he kept up a correspondence with several pastors of Acadian parishes in the the Maritimes. All this was taking place before 1890.

Although means of communication had already long existed, travel was becoming easier between New England and the Maritimes. Already, in 1855, there was steamer service between Boston and Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. In New Brunswick, a railway opened between Moncton and Saint John in 1860; then, in 1871, it was extended all the way to Bangor where it connected with the American rail system. As for Prince Edward Island, an oceanic link was established in 1864 between Charlottetown and Boston.

In 1890, the collège Sainte-Anne opened its doors at Church Point in Nova Scotia and some Acadian families of New England egan to enroll their young boys. The trip from Boston was easy since the collège was only a few miles from Yarmouth. From my own experience, I can tell you that when I entered the collège about thirty years later, a certain number of Acadian students from New England still studied there: ten in 1911, twenty-three in 1923, sixteen in 1924, ninteen in 1925. That practice continued for many more years. During the first three of the years listed above, the students came from different areas of Massachusetts, namely Beverly, Boston, Cambridge, Cape Cod, Chelsea, Dorchester, East Boston, Fitchburg, Gardner, Ipswich, Lowell, Lynn, New Bedford; there were also some from Waterville, Maine, from Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and one from New Hampshire.

Among the students who attended le collège Sainte-Anne, at least from 1897 up to 1954, all told, the seventy who attended came from thirty-four different cities of Massachusetts. There were a few from Brownsville and Waterville, Maine, and from Dover and Portsmouth, New Hampshire; some also came from Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and from Hartford and Cromwell, Connecticut, and we must not forget that there were also a number of young Acadians from New England attending le collège Saint-Joseph of Memramcook.

This leads us to ask ourselves where the Acadians from the Maritimes settled in New England. At first, they chose Massachusetts, particularly Lynn and Salem, in addition to Gloucester and Boston. A little later, toward the beginning of the twentieth century, and more particularly at the end of World War I, when imigration reached its apogee, Acadians from Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia, chose the northern suburbs of Boston, beginning with East Boston; then came Andover, Chelsea, Everett, Malden, Melrose, Reading, Saugus, Stoneham, Wakefield and Wilmington. The Acadians of Digby County chose instead the southern suburbs of Boston; Braintree, Dorchester, Milton, Quincy, and Weymouth. As for the Acadians of Cape Breton, particularly those of Cheticamp and Arichat, they settled mainly in Cambridge, although a sizeable number from Madame Island are found in Gloucester. The Acadians of New Brunswick tended to settle in manufacturing centers. Those from the Memramcook area grouped themselves in Waltham and Lynn; those from Saint Paul likewise went to Lynn, and also to Leominster and Gardner. In Gardner you can still find Acadians from Bouctouche and Saint-Antoine; those from Saint-Louis de Kent settled especially in Waltham and in Worcester. In addition, many Acadians from Westmorland County and the southern part of Kent County went to southeastern Massachusetts, to Brockton, Taunton, Fall River, and New Bedford mainly, because of the many textile mills. Sixty years ago, there were already six hundred Acadian families in New Bedford, five hundred in each of Lynn, Fitchburg and Gardner, two hundred in Cambridge, one hundred fifty in Newton and Waltham, and so on.

At first, the Acadians of northern New Brunswick did not emigrate proportionally in such great numbers as those mentioned above. Those who came settled in Cambridge along with those from Cape Breton, but subsequently, they were to be found in the area of Springfield, Chicopee, and Holyoke, Massachusetts. Even though one finds today a goodly number of Acadians in New Hampshire, as well as in Rhode Island and Connecticut, immigration to these States took place after the migration to Massachusetts and was never as large.

One can readily understand why organizations for the protection of Acadians as a people did not get their start in manufacturing centers; in such locations, Acadians were chilefly laborers whose love of culture was not higher than average. At the beginning of this century, though, there were already some Acadians who had climbed through the ladder of success in business. If a large number of Acadian professionals did not yet exist, we do find Acadians who had begun to exercise a beneficial influence on their own people.

The first attempt at organizing the Acadians of New England in a permanent fashion and on a large scale dates back to the early days of this century. The aim was to unite them, not so much by appealing to their patriotism, but by the more subtle means of playing up the financial benefit they might derive from joining. The goal was to create a financial institution, an insurance company which would be their very own. From this concept arose La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption. It has been said that the Acadians of New England, having already lived for a time in the United States, had become more adept at business matters than their counterparts in the Maritimes who had never hit upon this idea although they already had their own national society: La Société l'Assomption. Although this society had taken root in 1880 at the French-Canadian Convention of Quebec, which seventy Acadian delegates had attended, it was really founded in 1881 at the Memramcook Convention. From the beginning, the membership included Acadian names which, soon afterwards, would be found in New England. These are the people who dereamed of adding to it a society or company for insurance protection quite distinct from La Société l'Assomption itself.

In April 1902, Ferdinand Richard, who was the secretary of La Société l'Assomption, convened at Waltham a small assembly to which Fitchburg, Lowell, Lynn, New Bedford, and Worcester sent delegates. It was decided to meet again in Waltham, on the following August 15th to discuss the matter in convention. A very large number of Acadians from all parts of New England responded to the call. When Ferdinand Richard presented his plan of an insurance company for Acadians, he easily won the support of influential Acadians, such as Messrs. Jean H. LeBlanc and Clarence Cormier, president and secretary of the committee. Another meeting took place on May 30, 1903, this time in Fitchburg, at which it was unanimously voted to establish a mutual benefit society for Acadians. The name given to it, La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption was to distinguish it from La Société l'Assomption which had been founded more than twenty years earlier and which would later take the name La Société Nationale l'Assomption.

The new society held its first meeting on September 8, 1902, in Waltham where the national headquarters were located. The following year, in 1904, at the first congress of La Société Mutuelle, which was held on August 15 at Waltham, it was announced that the new society already numbered nine branches, seven in Massachusetts, one in Maine and one in Bouctouche, New Brunswick. It had 454 members in all. The second general meeting of the Mutuelle was held the following year, 1905, at Fitchburg. The next one, in 1906, was held in New Bedford, Ma and during all those years, the new society spread throughout New England. Even though it had an American founding, it was penetrating even more rapidly in the Maritimes than in New England. By 1907 there were already forty-two branches in the Maritimes compared with sixteen in the United States. Then the decision was taken to transfer the headquarters from Waltham to Moncton, New Brunswick. This took place in 1914. The transfer did not sit well with a number of Acadians in New England and two thousand of them withdrew from La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption to form a new mutual benefit society which was named La Société Acadienne d'Amérique, with Elphège Léger of Fitchburg at its head. At the start, the new organization met with great success and so did its annual conventions which were attended by representatives from all parts of New England. However, only a dozen branches were ever formed. La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption still remained too vigorous through New England for the newcomer to last. After a dozen years or so, fifteen at the very most, it went out of existence and was absorbed into La Société Mutuelle l'Assomption.

It is fair to say that during the first half of the twentieth century there was perhaps no other oganization that did as much for Acadian survival as did La Société Mutuelle in the Maritimes, as well as in New England, when each branch held almost monthly meetings. In Waltham and Gardner, two branches existed. There was one in each of the following cities: Amesbury, Cambridge, Everett, Fisherville, Fitchburg, Lawrence, Leominster, Lynn, New Bedford, Newton, Reading, Springfield, and Worcester, all in Massachusetts; Bridgeport, Hartford, and Norwich in Connecticut; Berlin and Nashua in New Hampshire; and Lewiston and Skowhegan in Maine. Sad to say, these branch offices were all suppressed in the 1960s. It can be stated that those years of the first half of the century were the most beneficial to the Acadian survival in New England.

Acadian activities were faltering when I arrived in New England in the first days of 1952. Some Franco-Americans were still maintaining the culture brought from Quebec. So, I did like other Acadians and joined these organizations and societies. By appearing at meetings, and by making myself heard, people began little by little to look upon Acadians as having a identity distinct from their own, an identity which should be acknowledged. Among these organizations, should be mentioned Le Comité de Vie franco-américaine, La Société historique franco-américaine, the Richelieu Clubs, the Franco-American federations of the various New England States, and more recently the national Franco-American conferences which initiated annual voyages between New England and Louisiana. These organizations have always included Acadians among their membership. Here I wish to make special mention of Le Travailleur; in this newspaper, Wilfrid Beaulieu, a descendant on his mother's side of the Acadian family of D'Amours, published a great many articles about Acadians and he did so over a long period of time.

However, the society which was destined to do the most for the preservation of the Acadian heritage in New England was not located in New England but in Moncton, New Brunswick. I am referring to La Société Historique Acadienne which was founded in 1960. Almost from its foundation, it included twenty-four members from New England and New York. These members could not, unfortunately, attend the meetings which were always held in the Moncton area. The Société did publish a magazine that the members derived the most benefit.

[Webmaster's Note: recently, the Société Historique of Moncton has set up a wonderful web site!] One day, I said to myself, why couldn't we have our own meetings in New England? So, in the Fall of 1966, two of us went to the annual meeting of the Society to present our proposal. The keen interest which it generated among the members present, and the enthusiastic approval accorded to it by the executive committee, were more than sufficient to launch our project. Subsequently, in 1966, the New England group of La Société Historique Acadienne was founded. This was not a new society but simply a grouping of the members residing in New England who already belonged to La Société Acadienne.

This organization was very successful during its twelve-year existence. Within a few years, one hundred eighteen new members joined the original twenty-six. I realized very quickly that the reason they joined us was to learn more about the history of their Acadian forebears. At this point I can say that many of these members were experiencing their first contact with Acadia. They subsequently often visited old Acadia, going to the places where their ancestors had settled either before the Deportation or after it, and from which they had emigrated to settle in New England.

For twelve years, we held four meetings each year in the vicinity of Boston, at which a formal lecture was delivered. I had noticed that only one-third of the members could speak French well. Another third understood it, but could speak it only with some difficulty. The final third could neither understand nor speak the language. For that reason, most of our meetings were conducted in English. But the call to each meeting and the minutes were always issued in both languages. The lectures always developed an Acadian topic history, genealogy, geography, customs, mores, language, literature, and so forth. There were about forty-five of them all told.

One of the goals which the group had set for itself from the start was the restoration of Saint Croix Island. We worked on that project with a will. The voluminous correspondence which I have kept is proof of this. We corresponded with senators and representatives in Washington, with the directors of the National Park Service, particularly Acadia National Park at Bar Harbor, and with individuals from Calais, Maine, just to mention a few. In November 1969, a number of us went to Saint Croix where we joined with members from Moncton who had come to meet us. We had gone there, not only to visit the island, but especially to promote the restoration project. We had agreed to meet in Calais with the authorities of National Park Service at Bar Harbor.

In Augusta, we held a meeting, at which the Governor's administrative assistant presided, with six directors of parks, museums, the arts, and the Historical Commission of the State of Maine; a representative of the University of Maine at Orono was also present as well as the librarian of the Maine Historical Society of Portland. I believe that our group had much to do with the ongoing efforts to succeed in restoring Saint Croix Island to the appearance it has at the time of De Monts and Champlain.

The greatest success of this group during its twelve-year existence occurred during the American Bicentennial Celebrations in 1976. On that occasion, then Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts decided that every ethnic group in that state should have its day of celebration at the State House in Boston. The last week in May was reserved for the francophone groups. Three weeks before, the governor had issued a formal written proclamation setting aside Monday, May 24, as Acadian Day in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Permission had even been obtained to fly the Acadian flag from morning to evening of that day in front of the State House, side by side with the American flag and the flag of the Commonwealth.

The New England Group of La Société Historique Acadienne was, nonetheless, moving toward intoning its swan song. After having organized, for the end of June and the beginning of July, 1979, one last excursion to Saint Croix Island, to mark the 375th anniversary of the arrival there of De Monts and Champlain and their party, there fell to me the painful and thankless task of announcing that the group no longer had the wherewithal to continue functioning.

[The group managed, nonetheless, to maintain itself for a few years as an affiliate of the American-Canadian Genealogical Society of Manchester, N.H., where it was known as L'Association généalogique et historique acadienne de la Nouvelle-Angleterre. Today, it is an independent group known as The Acadian Cultural Society/Société culturelle acadienne, with nearly seven hundred members. Its headquarters are in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where it publishes a quarterly called Le Réveil Acadien-Editor's note]

After all that has been stated, it is not presumptious to speak of an Acadian survivance/survival in New England. The worthy sons and daughters of Acadian immigrants have forgotten neither the tragic history of their deported ancestors, nor the more immediate past, that of their families who came to New England within the last 100 years or so in search of a better life for themselves and for their children and grand-children.

N.B. This article was originally written by Father d'Entremont in french. It was translated by Reverend Alexis Babineau, A.A. for inclusion into Steeples and Smokestacks.

The above article first appeared as La survivance acadienne en Nouvelle-Angleterre in the French Institute's publication entitled L'Émigrant acadien vers les États-Unis 1842-1950.

Father d'Entremont approved its inclusion in the Institute's publication.

Permission to reproduce this article that was published in "Steeples and Smokestacks" A collection of essays on The Franco-American Experience in New England, Claire Quintal, editor, was received on 2 August 2000 from Leslie Choquette.

This work was published by the Institut Français of Assumption College, Worcester, Massachusetts. ISBN 1-880261-03-0

The following was sent to Leslie by Richard Fortin, a fellow-member of the American Canadian Genealogical Society.

"Hi Leslie,

I am contacting you on behalf of Lucie LeBlanc Consentino who has a website called Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home

I am requesting the Institute's permission to reproduce on her home page an article that appeared in Steeples and Smokestacks on the New England Acadians, originally authored by Father Clarence d'Entremont as presentation at an Acadian colloque some years back.

The article is probably the best documentation of the post dispersion emigration and settlement of the Acadians in Southern New England and could be of value to those researching and looking for families especially in Massachusetts.

Knowing Lucie as I do I am sure that if she was granted permission she would give appropriate credit where it is due.

Please advise if that is possible and I will forward your comments to her.

Thanks,

Richard Fortin"

RESPONSE: "Bonjour!

Yes, please feel free to reproduce the article. We ask only that you include a full reference to Steeples. Congratulations on what sounds like a very fine website.

Sincerely,

Leslie Choquette"

This is pretty much what it was like going to Salisbury Beach in the summer - perhaps even more crowded than this postcard shows. Lots of people who arrived as early as they could to get the best spot on the beach, which of course, was as close to the water as possible at low tide but not so close as to get wet when the tide rolled in.

This is pretty much what it was like going to Salisbury Beach in the summer - perhaps even more crowded than this postcard shows. Lots of people who arrived as early as they could to get the best spot on the beach, which of course, was as close to the water as possible at low tide but not so close as to get wet when the tide rolled in. Hampton Beach was just a little way further up the road. This is an old postcard because I do not remember the wooden rails on this bridge. By the time I was born it was a very architecturally finished concrete bridge with huge pillars into the ocean floor. This bridge would take us right into Hampton Beach from Salisbury. At the time our family prefered Salisbury - you can just imagine the one lane traffic crossing that bridge in the summer!

Hampton Beach was just a little way further up the road. This is an old postcard because I do not remember the wooden rails on this bridge. By the time I was born it was a very architecturally finished concrete bridge with huge pillars into the ocean floor. This bridge would take us right into Hampton Beach from Salisbury. At the time our family prefered Salisbury - you can just imagine the one lane traffic crossing that bridge in the summer!

This is a very early postcard of the pier at Old Orchard Beach, Maine. If you look closely at the clothes people are wearing, it looks like the early 1900s. We never went to Old Orchard until I was about ten or eleven years old and we had our own car. Today it is only 1-1/2 hours from home via the Maine Turnpike. In the 1940s it took four hours via Route 1 all the way through cities and towns.

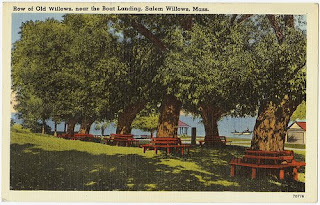

This is a very early postcard of the pier at Old Orchard Beach, Maine. If you look closely at the clothes people are wearing, it looks like the early 1900s. We never went to Old Orchard until I was about ten or eleven years old and we had our own car. Today it is only 1-1/2 hours from home via the Maine Turnpike. In the 1940s it took four hours via Route 1 all the way through cities and towns. Salem Willows was another of our favorite places in the summer. You can see from the willows in this old postcard why it was called Salem Willows and it is located in Salem, Massachusetts well known for the Witch Trials. Ironically, today one of our daughters lives nearby and she and her husband go to Salem Willows with their little boy just to walk and see the ocean. Every time we went there my mother would purchase salt water taffee and we could watch it being made.

Salem Willows was another of our favorite places in the summer. You can see from the willows in this old postcard why it was called Salem Willows and it is located in Salem, Massachusetts well known for the Witch Trials. Ironically, today one of our daughters lives nearby and she and her husband go to Salem Willows with their little boy just to walk and see the ocean. Every time we went there my mother would purchase salt water taffee and we could watch it being made.